Purpose

Tax expenditures are provisions in the tax law designed to benefit specific groups of taxpayers. They are similar to spending programs but generally do not involve direct federal outlays. Rather, they work through the income tax system, taking the form of special credits, exemptions, deductions, exclusions, and preferential rates. This study estimates the utilization of federal tax expenditure provisions by small and large businesses in 2013.

Background

By design, most tax expenditures provide incentives for taxpayers to engage in, or increase their contribution to, activities in which they ordinarily would not engage in the absence of the provision. For example, some of the largest federal tax expenditures involve incentives for home ownership (e.g., the mortgage interest and property tax deductions), investment (e.g., accelerated cost recovery for equipment and structures), healthcare (e.g., exclusion for employer-provided insurance), and research (e.g., expensing of research and experimental expenditures).

Tax expenditures are typically viewed as tax loopholes or special tax breaks for limited classes of taxpayers. However, many of the provisions identified as tax expenditures are broadly available to individual or business taxpayers.

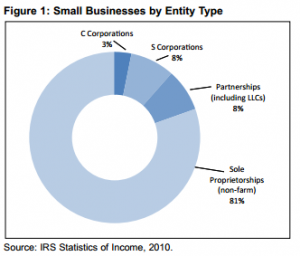

The complete picture of the use and impact of tax expenditures by small businesses requires examining the legal form of a small business and the tax advantages afforded each entity type under the tax law. About 80 percent of small businesses organize as sole proprietorships and report their income, deductions, credits, and tax liability on Form 1040 (Schedule C) (Figure 1). Another 16 percent of small businesses are pass-through entities such as partnerships and S corporations and report their taxable income on Form 1040 (Schedule E). The 3 percent of small businesses that organize as C corporations report their business income and taxes on the Corporate Income Tax Form 1120. Among larger firms, 50 percent are S corporations, 25 percent are C corporations, and 25 percent are partnerships (including LLCs).

The federal tax treatment of company profits differs for C corporations versus S corporations, partnerships and sole proprietorships (which are often called pass-through entities). The C corporation rather than the shareholders of the company pays taxes on its profits.[1] In contrast, the profits and expenses of the pass-through entities are allocated to their owner(s) and taxed at the individual’s income tax rates.

This research looks at tax expenditures for each legal form and the tax advantages afforded each under the tax law. The study defines small business as: S corporations, partnerships, or sole proprietorships with less than $10 million in gross receipts and C corporations with less than $10 million in assets.

Overall Findings

In 2013, the largest federal tax expenditure provisions utilized by all businesses accounted for an estimated total of $161 billion.[2] This study finds that small businesses use approximately $40 billion, or 25 percent of the total. Small businesses benefit from different tax expenditures than larger businesses.

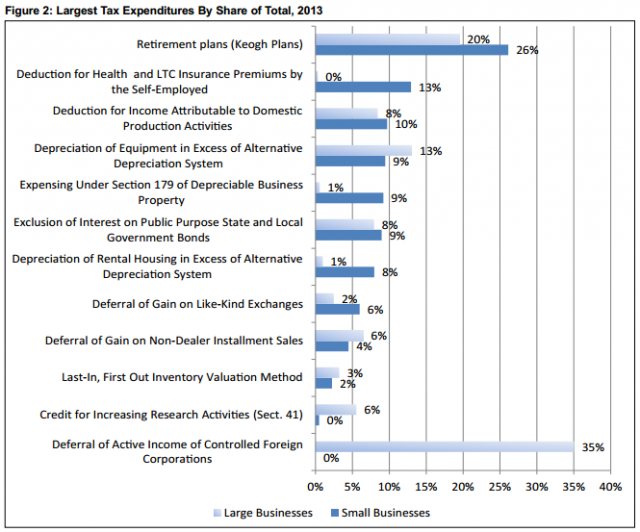

One area in which there is a difference is employer contributions to employee retirement and health benefit plans. Under current law, these contributions are tax deductible business expenses for both C corporations and certain pass-through entities. However, for the C corporation, the employer’s contribution for retirement and health insurance premiums is not counted as taxable income to the employee, and therefore is not considered a tax expenditure to the firm. In contrast, because many of the owners of pass-through entities are also the firms’ employees, there are significant tax expenditures for the deductions for retirement and health insurance premium contributions by these sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations (Figure 2). This study finds deductions for retirement (Keogh) plans were about one-fourth (26 percent) of all of the large federal tax expenditures for small businesses in 2013. Deductions for health and long-term care premiums by the self-employed represented an additional 13 percent of federal tax expenditures in 2013.

Other tax expenditures that benefit small businesses were enacted or expanded specifically to encourage U.S. domestic manufacturing and investment. For example, the deduction for domestic production activities (also referred to as the manufacturer’s deduction) was enacted under the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-357). Under this provision, companies receive a deduction for certain activities conducted in the United States (e.g., manufacture of tangible personal property, software development and production of electricity, natural gas in the United States).[3] In 2013, 10 percent of the largest tax expenditures for small business were for domestic production activities (compared with 8 percent for larger firms).

Another tax expenditure that was intended to promote investment by small businesses is Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Sec. 179, which was expanded under a number of economic stimulus laws over the past decade.[4] Sect. 179 allows small businesses to expense assets as they are purchased instead of depreciating them over several years. By its operation, this provision is available only to small businesses and cannot be utilized by larger businesses. In 2013, 9 percent of the largest tax expenditures for small businesses were for the Sect. 179 deduction (compared with 1 percent for larger firms).

The largest tax expenditure for large firms provides no benefit to small firms in the United States. More than one-third of tax expenditures for large firms are for deferral of active income of controlled foreign corporations (Figure 2). As a general rule, only large multinational corporations have controlled foreign corporation operations and therefore have foreign income for which this deferral is available.

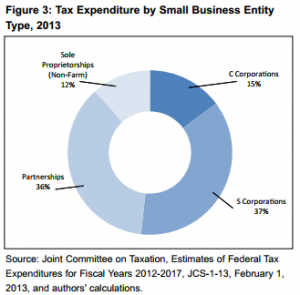

Small business utilization of tax expenditures is dominated by the 16 percent of small businesses organized as partnerships and S corporations (Figure 3). This statistic is likely more reflective of the higher relative incomes attributable to these entities than to the nature of the tax expenditures. Conversely, the 80 percent of small businesses organized as sole proprietorships use only 12 percent of small business tax expenditures in 2013.

Policy Implications

Recent discussions of tax reform have focused on repealing most tax expenditures as part of an effort to create a simpler and fairer tax system. However, most tax expenditures remain part of the tax code for specific reasons and with particular objectives (e.g., increased investment), and removing these provisions could cause unintended economic disruption.

Moreover, the standard approach to measuring tax expenditures generally overstates the revenue associated with repealing the provision. Policymakers may suggest that repealing particular tax expenditures will increase revenue to the federal government by the sum of the individual provisions. However, these estimates based on repeal of tax expenditures differ significantly from revenue estimates by omitting the behavioral response that would likely accompany repeal of the provision. If multiple tax expenditure provisions were repealed as part of the same tax legislation, it is likely that the changes would create interaction effects. When these interactions are considered, the total revenue change is generally less than the sum of the separate provisions.

Methodology

This research relies primarily on Quantria Strategies, LLC’s individual income tax simulation model to calculate the utilization and value of major tax expenditure programs that affect sole proprietorships, partnerships (including LLCs) and S corporations. The basis of this model is a stratified random sample of individual income tax returns filed by U.S. taxpayers. To this dataset are added demographic, employment, and labor force information from the Current Population Survey (CPS). A fundamental component of the model is a computer program that performs detailed calculations of the tax liability of each taxpayer given the tax law and parameters (e.g. tax rates and brackets) in place for the current year of analysis.

This report was peer-reviewed consistent with Advocacy’s data quality guidelines. More information on this process can be obtained by contacting the director of economic research at [email protected] or (202) 205-6533.

[1].The shareholder may pay taxes on corporate dividends.

[2].The largest tax expenditures are defined as those tax expenditures where the sum exceeds $500 million in the most recent year.

[3].For details on specific deductions under IRC Sect. 199 see www.irs.gov/irb/2005-07_IRB/ar08.html.

[4].These include the 2008 Economic Stimulus Act, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment Act of 2010, Small Business Jobs and Credit Act of 2010, and the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, Job Creation Act of 2010.